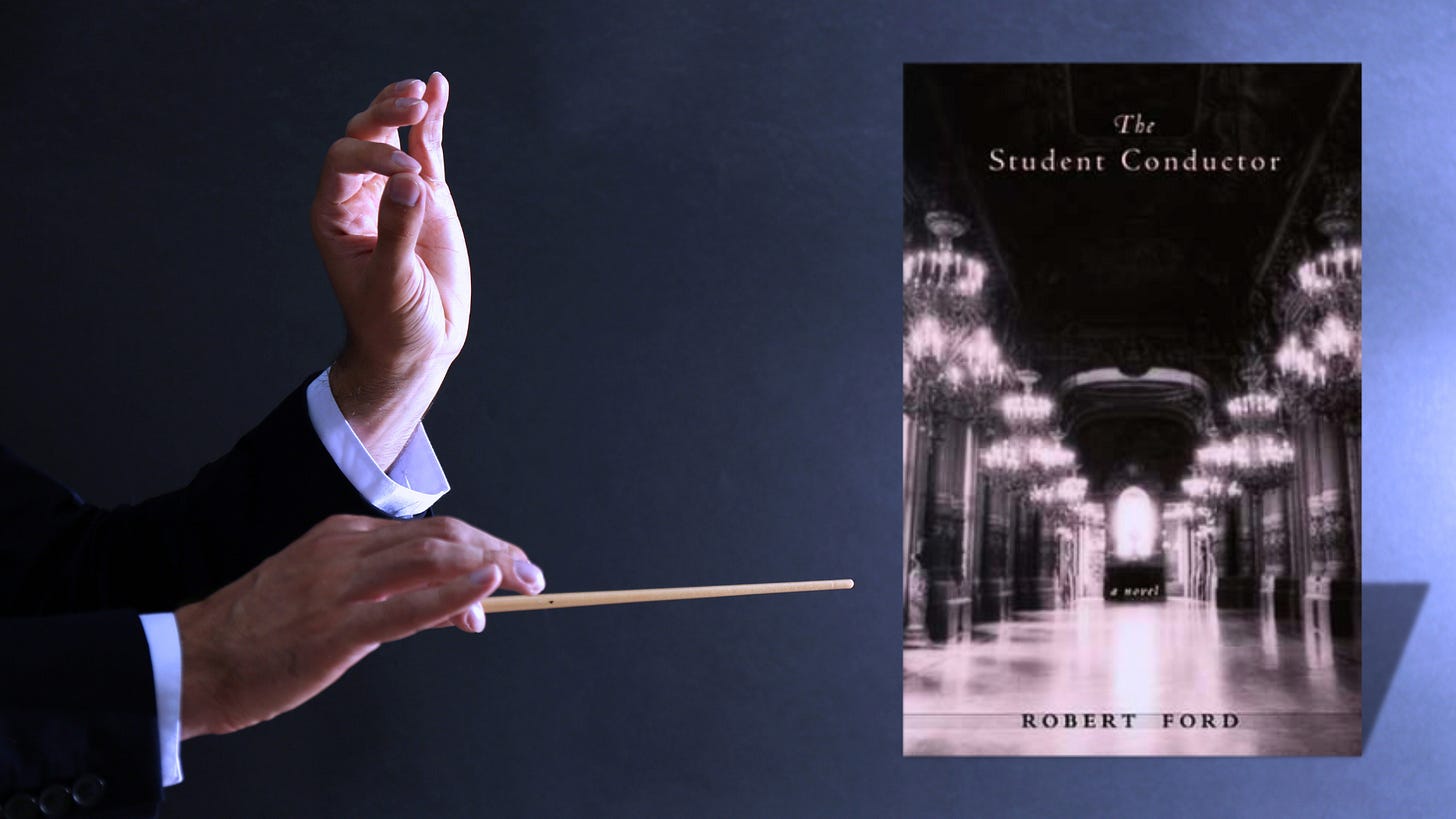

The Student Conductor by Robert Ford

The Student Conductor is a touching, bittersweet story of a man learning how to pursue the things he loves—and what could stop him from doing so.

This is not a review. See why.

Context

It’s 1989, just before the fall of the Berlin Wall. American conducting student Cooper Barrow arrives in West Germany to study under master conductor Herr Ziegler. Barrow is returning to the craft after dropping out of Juilliard and spending eight years teaching violin in a small town in upstate New York. While in Germany, he learns about music and life, both from his teacher and from the musicians he works with—especially the oboist Petra Vogel, an East German defector he falls for. Through Ziegler’s and Petra’s examples, he learns about the devastation guilt can cause and the importance of being ambitious and having confidence in oneself.

Key Ideas

Confidence is necessary for success

Guilt can lead to self-sabotage

Confidence is necessary for success

Barrow has remarkable potential as a conductor. As he studies scores, rehearses with the student orchestra, and implements Ziegler’s feedback, he grows toward that potential. But he’d been at the best performing arts university in the United States before that, with numerous mentors and learning opportunities. Why move to Germany? Thinking he had done poorly at a concert, he ran off before finishing the performance or his degree. He was afraid that the concert was indicative of his ability, so he let his doubt get in the way of his success—and then let that error stifle his potential for nine years.

Ziegler knows Barrow’s history, and quietly tries to teach the younger man the importance of taking charge. Eventually, Ziegler puts Barrow to the test, letting him demonstrate that he does trust his abilities and will do what it takes to succeed as a conductor. This means not merely studying scores, absorbing Ziegler’s teachings, and rehearsing, but taking control of a situation—making firm decisions, being confident, and leading when it’s time to. Ziegler holds that to conduct is to “lead people to their souls”—to connect a physical sensation, sound, with emotions. There is much more to it than just waving a baton. “You know this,” Ziegler says to Barrow, “and this is why you are afraid, either to take a stand or to conduct this concert. You stand down.” But when he chooses to conduct, he “open[s] cages” for musicians to perform at their best and for the audience to connect with the music when he conducts well (270). At this climactic moment, Barrow must choose what kind of conductor—and what kind of person—he will be.

Guilt can lead to self-sabotage

Another lesson Barrow learns from Ziegler is the destructive nature of guilt. Ziegler normally has an incredible ear for which musicians ought to be playing which parts in a piece of music, choosing the best available so the end result is remarkable. But he removes their best oboist, Petra, from her leading part and places a less-accomplished musician in her place. The decision is completely bewildering to Barrow and his fellow student conductors. At first, Barrow speculates that it’s to punish him for disobeying Ziegler’s instructions during a rehearsal which the maestro was absent from. But later, he and his colleagues realize it’s part of a pattern: Whenever Ziegler is preparing to perform a Brahms work, he always causes some sort of problem, some way of reducing the quality of a magnificent performance. Why would he do such a thing?

Barrow eventually learns that Ziegler is burdened by unearned guilt from his experiences during World War II and that Brahms’s work reminds him of that guilt. He feels like he doesn’t deserve to be associated with a phenomenal production of a Brahms piece, and so he makes sure that he never is. The guilt is unearned in this case because the Nazis forced him to make an impossible decision (which I won’t spoil); people would have suffered no matter what he did. But, as with many others who suffer from some form of survivor’s guilt, Ziegler struggles to regain a sense of an understandable world in which he is efficacious by taking responsibility for something he couldn’t have actually controlled. Similarly, Petra (the oboist) struggles with guilt related to her defection from East Germany, which contributes to self-sabotaging in her personal life as well (the specifics of this would be a major spoiler, as we only discover them at the end of the book). One of the key things Barrow must learn is to not let fear or doubt get in the way of his success and happiness the way two people he admires, Ziegler and Petra, let guilt get in the way of theirs.

Conclusion

Barrow’s story is one of personal growth, in which he discovers how one’s self-esteem—detracted from by guilt, or built by confidence and ambition—affects one’s career and one’s personal life. It’s a touching, bittersweet story of a man learning how to pursue the things he loves—and what could stop him from doing so.

Acknowledgement

This book was a gift from my friend and colleague Jon Hersey. Jon studied music production in college and worked in recording studios in Nashville before turning to his current career, which includes writing, editing, teaching, and making YouTube videos discussing and evaluating music. He mentioned particularly adoring the book’s beautiful descriptions of music. As a brief example: “the celli crossing down through the bassoons, hiding under a shimmer of winds, resurfacing.” A huge thanks to Jon for the thoughtful gift!

Thanks for writing this, Angel! It's so nice to relive this story in short-form. I don't think Robert Ford has written another novel, but I wish he would.