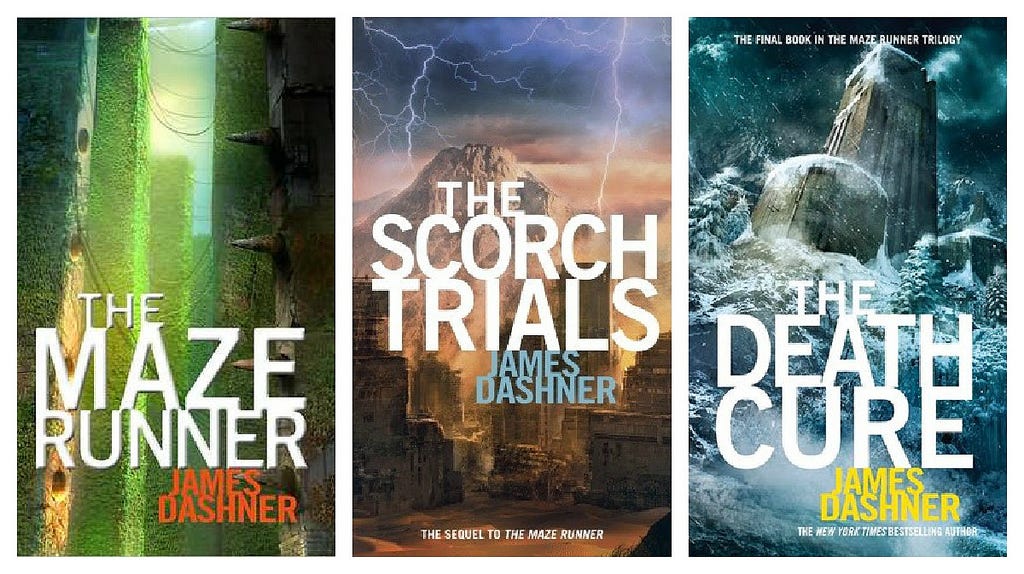

The Maze Runner trilogy by James Dashner

The Maze Runner trilogy is action-packed, but the action isn't well-integrated with the characters, making for a not particularly profound read.

The purpose of this Substack is to reflect on the ways fiction authors express their philosophical ideas in their works. Where possible, I will integrate those themes with other ideas and evaluate them. Though I may occasionally comment on various aspects of the writing, these articles are not reviews. For those who are unfamiliar with the works discussed, I will include the relevant details from the story in the “context” section, so if you are familiar with the work, I recommend you skip that section. I will try to avoid the most important spoilers, but there will be some, as it is often impossible to properly analyze the meaning of a story without accounting for how it ends.

Context

In the first book, Thomas wakes up in the center of a maze with much of his memory missing. He discovers that a group of boys has been surviving on their own in this walled area, called the Glade, and trying to get out of the maze for two years (the latter task is assigned to the “Runners,” who map the maze each day). This group is led by Alfie, with Newt as second in command. The maze beyond the Glade is home to horrific creatures dubbed “Grievers” who threaten any boys who stay in the maze after dark. The book ends with most of them finally escaping the maze and being rescued from the facility they find themselves in.

In the second and third books, we gain a lot more context for who made the maze and why the boys were in it. The outside world suffered an environmental catastrophe that has made large swathes of the Earth uninhabitable, accompanied by a pandemic known as “the Flare” that drives its victims insane. In response, various surviving governments banded together to form WICKED (World In Catastrophe: Killzone Experiment Department) to find a cure for the Flare. The purpose of the maze was to study the brain patterns of a number of individuals, some of whom are immune to the deadly virus and some of whom aren’t, in a wide variety of circumstances. The intent was to use these data to create a cure.

In the second book, the boys find another trial group (of girls) who’ve been subjected to the same treatment. The groups must complete another trial—this time a march through a desert inhabited only by victims of the Flare. In the third book, Thomas and his friends break free from WICKED’s clutches, attempt to hide in a disease-ridden city, join a rebellion, and eventually end up in a final showdown with WICKED leaders.

Major Ideas:

The ends don’t justify the means

It’s important to look out for your friends

Evaluation: Too much action divorced from ideas

The ends don’t justify the means

If the lives and health of millions are at stake, is it justified to sacrifice the lives of a few? This is the central moral question of the trilogy. Broadly speaking, the government agency (WICKED) has decided that the answer is yes—the ends justify the means. They have taken over the lives of Thomas and his friends, along with those of other test subjects, in the belief that doing so is justified if it enables them to find a cure. And from a utilitarian perspective (the philosophy that the moral ideal is “the greatest good for the greatest number”), this is right. As one WICKED agent puts it, “the lives of a few [are] worth losing to save countless more. . . . The end can justify the means” (The Death Cure, 9).

Although we see great suffering being inflicted by the Flare and the environmental damage, which may lead some people to say the crisis must be solved at any cost, the perspective the author sympathizes with most is Thomas’s—the sacrificial victim in this scenario. Though he pities those who get sick with the Flare, he doesn’t trust WICKED (who have lied to and manipulated him and his friends repeatedly) to solve the problem. He had helped WICKED as a brainwashed teenager, but his experiences in the maze and later trials have changed his mind: “Living through this kind of abuse is a lot different than planning it. It’s just not right” (The Death Cure, 9).

This is true, but Thomas doesn’t ever explain why; he merely feels that it is because he’s been the means to WICKED’s (seemingly good) end. The story misses the fundamental point that the reason nobody should be sacrificed for the good of a group is that each individual has a right to his or her own life. A society, on the other hand, is not alive and has no rights. Many feel or think that society is valuable in and of itself, but value doesn’t exist without valuers; it isn’t inherent in anything. Society is a value—insofar as it improves or serves the lives of the individuals within it. But if instead it takes those lives away (whether by literally murdering them or by taking over their lives), it is destructive and anti-life. Sacrificing even one person for the good of others violates rights and is deeply wrong.

It’s important to look out for your friends

Thomas’s primary motivation throughout the series is the wellbeing of his friends—those he was in the maze with (the “Gladers”) and those he meets later in his journey. He takes great risks for those friends, from staying out in the maze late at night and being attacked by Grievers in order to save Alfie in the first book to going into a camp of Flare-infected maniacs to save Newt in the third. It’s touching that he values his friends’ wellbeing highly enough to prioritize it, and many readers can relate to this motivation.

However, it is notable that Thomas doesn’t actually know these people that well; he’s forced into proximity with them via WICKED’s machinations, and the affection he feels for them seems primarily based on having survived difficult things together as opposed to shared values and goals. Many beautiful friendships formed on this basis exist in popular literature. Consider the Fellowship of the Ring (particularly Sam and Frodo) in The Lord of the Rings, who share the goal of destroying the ring to preserve their freedom from the evil Sauron who sought to enslave them. Though their short-term goal is survival, they have values they care about and want to protect (people back home, a legacy to fulfill, a love), not just disvalues they try to avoid. Or think of the Golden Trio in Harry Potter, who value love, truth, and justice, and fight together for those values against the amoral and deeply prejudiced Voldemort. Friends can be a rational and important value in a person’s life, but only when they’ve earned that respect and admiration.

Evaluation: Too much action divorced from ideas

This trilogy is very action-heavy. Though there’s room for individual preference on how much action a person enjoys in their fiction, the books included many long action sequences that often substitute for the plot. The first book was practically all action, with the only question being who put the children there and why. The second book begins to answer that question and introduces a quasi-love triangle (which goes nowhere), but it is still about 90 percent action. In the third book, Thomas joins the rebels and actually makes a stand; only then is there some integration between the moral questions and the action involved, but still not enough for a thoughtful reader to ponder.

The intense action and the children being manipulated by a corrupt government have led the series to be compared to The Hunger Games (my editions even have “A must for fans of The Hunger Games” emblazoned on the cover of each book), but this similarity is sadly superficial. The Hunger Games series gets much more in depth on issues such as tyranny, integrity, and pursuing a variety of values than the Maze Runner books do.

Side Note

The trilogy has been adapted into three films; I found the books not interesting enough (and the second book disturbing enough) that I’ve chosen not to watch the films, and therefore cannot comment on them.

In Conclusion

The Maze Runner trilogy deals with the important moral question of whether the ends justify the means. Though it comes down on the right side of that question, it doesn’t do so in a particularly convincing way (would Thomas have changed his mind if he hadn’t been WICKED’s victim?). It contains a lot of action, but it’s not well-integrated with the characters, making for a not particularly profound read.

Your review confirms my impression of the series — and confirms my decision to skip reading it. That said, I thought the book had a great name. Maze Runner caught my attention the first time I heard it and made me quite curious. The general plot synopsis only added to my curiosity. But then my son started reading the books and telling me about them and that killed all interest. As you described, it seemed like too much action/horror drowning out a story that otherwise had a lot of potential.

I watched the first of the three films which didn't leave much of an impression beyond not caring to watch the others.