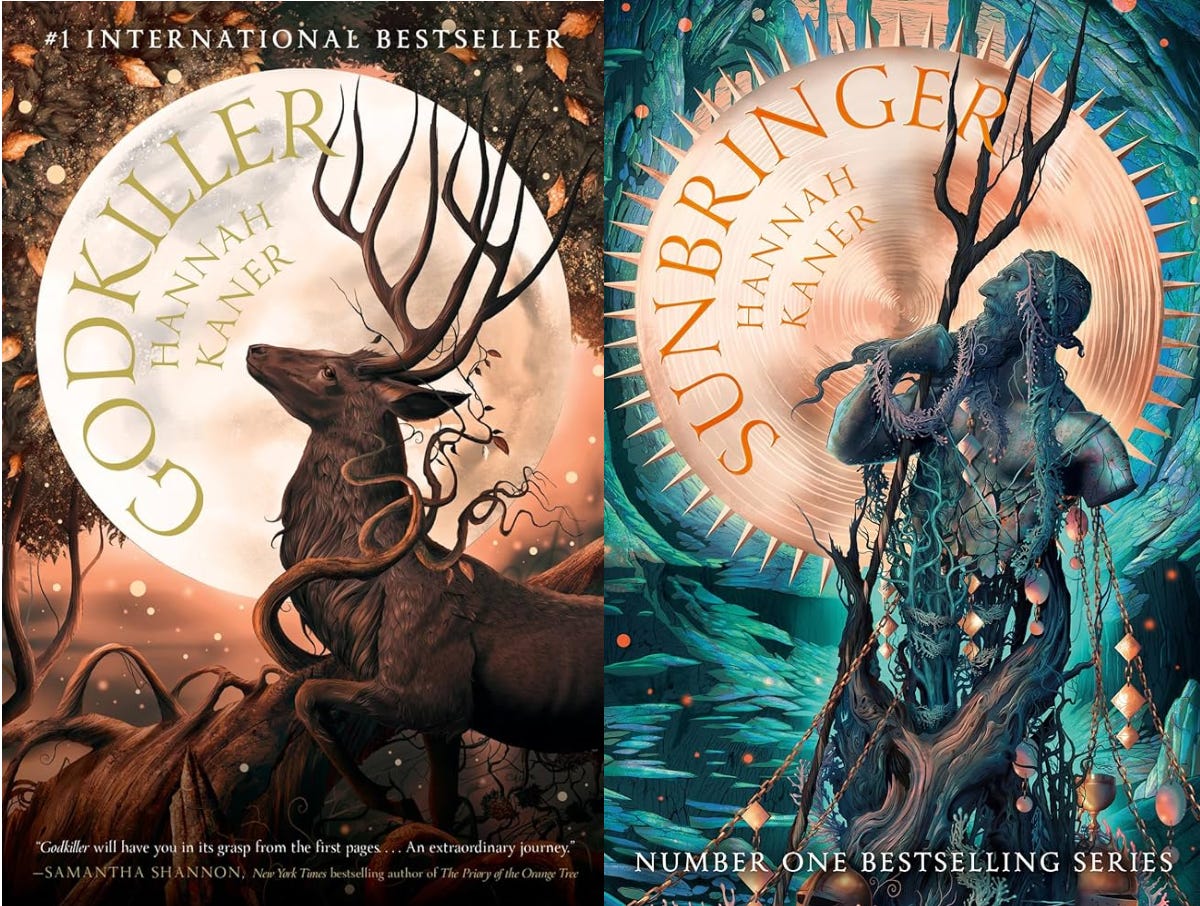

Fallen Gods by Hannah Kaner

The Fallen Gods series thus far has intriguing political and moral themes that are well-integrated with exciting fantasy worldbuilding.

The purpose of this Substack is to reflect on the ways fiction authors express their philosophical ideas in their works. Where possible, I will integrate those themes with other ideas and evaluate them. Though I may occasionally comment on various aspects of the writing, these articles are not reviews. For those who are unfamiliar with the works discussed, I will include the relevant details from the story in the “context” section, so if you are familiar with the work, I recommend you skip that section. I will try to avoid the most important spoilers, but there will be some, as it is often impossible to properly analyze the meaning of a story without accounting for how it ends.

Context

Imagine a world where gods are powerful beings created by human hopes and desires and sustained by prayers and sacrifices. This is the backdrop for Hannah Kaner’s ongoing trilogy, the Fallen Gods series. In that world, gods are created and made more powerful by human emotions, but will fade away if they’re forgotten. Though some provide benefits to humans, many demand a high price for their help, and most are more interested in gaining power than in keeping their word. This has led to serious consequences for the humans—culminating in a war that took place before the events of the first book, but which has deeply affected the country. Perhaps most notably, it led the victorious new king, Arren, to outlaw all gods.

We follow four characters: Kissen, a one-legged veiga (godkiller-for-hire) with a vendetta; Elogast, a deeply moral knight-turned-baker; Inara, the daughter of a noblewoman with unusual powers; and Skediceth, a god of white lies who’s bound to Inara.

In Godkiller, the four travel together to the site of the war between gods and humans. Kissen and Inara seek a way to sever the bond between Inara and Skediceth, whereas Elogast is on a mission from his former best friend, King Arren. In the book’s finale, the protagonists are pitted against a fire goddess whose lust for power has razed the lives of thousands.

In Sunbringer, the political themes come to the fore, with Elogast, Inara, and Skediceth seeking to undermine the power of the tyrannical Arren in a city of scholars. Meanwhile, Inara learns more about her past and Kissen battles a fierce fire deity threatening to consume a neighboring country before being deposited by a wind god amongst those rebelling against Arren.

Main Ideas:

Humans make and can solve their own problems

Having power over others is intoxicating—and morally wrong

Moral principles are more important than blind loyalty

Humans make and can solve their own problems

At first glance, it seems as if the gods are the source of most of the problems in the story, both in political terms and for many of the characters. Gods typically kill, destroy buildings, demand sacrifice, and generally wreak havoc. But it soon becomes clear that the truth is more complex than that. After all, the gods are created by human wishes and fears. They’re also sustained by their worshippers; if people stop worshiping a god and forget about him, he will slowly fade away to nothingness. But if people make more and bigger sacrifices (bigger meaning things that are more important to them), the gods become more powerful.

But no god is omnipotent. Veiga such as Kissen are dedicated to destroying gods who are causing problems for people who hire them. Gods have a kind of magic; they can cast curses, for example—but the curses can be broken. Given this context, the gods seem to be a metaphor for problems that humans create. Once a problem establishes itself, it can seem to take on a life of its own. The more you feed it, the bigger it gets; starve it, or confront it head on, and it diminishes. This is true for psychological issues, relationship problems, and larger societal issues. The inspiring aspect of the concept is that we aren’t condemned to suffer whatever fate the gods (or the problems in our lives that seem overwhelming) have in mind for us; we can challenge them and break their power. But that can’t be done just by wishing for it; just as in the real world, there are principles the characters must follow to create the effects they desire.

Having power over others is intoxicating—and morally wrong

Another aspect of the gods is that they tend to get progressively greedier as they get more powerful. Young gods are typically content with a few prayers and petty tokens, but older, more well-known gods begin to demand more—from important family heirlooms to animal sacrifices to, in some cases, human sacrifice. As the old saying goes, absolute power corrupts absolutely.

But the heroes know that having the power of a god (or being king) doesn’t make one above moral judgment. Kissen holds the gods responsible for both the destruction they wreak directly and the actions their faith-blind followers take on their behalf. Inara, too, doesn’t give gods a free pass merely because they’re gods. For example, Skediceth takes over Inara’s body at one point, and she treats this as a major betrayal; he has to work hard to earn back her trust.

Nor is this accountability limited to gods; King Arren is driven by a desire for power and the admiration of his people. He seems to want to replace the gods as the object of his subjects’ reverence, despite not doing anything to deserve it besides winning a war via underhanded tactics (he betrayed his allies). The more he sees his subjects admiring him, the more he takes it as his due and deals harshly with those who don’t act accordingly. We see the effects of his authoritarian rule on the pilgrims who worship in secret, on the scholars whose love of knowledge drives them to preserve histories of the gods, and on his own soldiers and nobles, none of whom are safe from his wrath.

Moral principles are more important than blind loyalty

Perhaps the most heroic character in the books is Elogast. He grew up with Arren and helped him win the war against the gods. But Elo put down his sword when Arren banned all the gods, holding that it was a violation of people’s freedom of religion to ban all gods (as opposed to only banning those who were actively causing problems). In Godkiller, he is deeply conflicted about the decision, because he feels deeply loyal to Arren; not only did they grow up together, but Arren saved his life at great personal cost during the war.

But at the end of the first book, Elo sees that Arren has become a tyrant and a danger to all, and he is willing to stand against him. He does so repeatedly in Sunbringer: He joins the rebel workers, convinces a local noble to support them, and organizes a stand against the king. When the confrontation comes, he must endure the king’s taunts of betrayal, which he does with ironclad conviction. Elo knows that morality requires loyalty to rational principles, not individuals who have ignored or betrayed their own conscience.

Conclusion

The Fallen Gods series thus far has intriguing political and moral themes that are well-integrated with the fantasy worldbuilding. Though the writing shows the debut author is developing, the characterization and fascinating ideas throughout make for great reads, and I look forward to reading the final entry in the trilogy when it’s released.

This sounds like my type of fantasy novel. A bit of a blend of Gaiman and Tolkien. And the up characters you describe sound intriguing: "Kissen, a one-legged veiga (godkiller-for-hire) with a vendetta; Elogast, a deeply moral knight-turned-baker; Inara, the daughter of a noblewoman with unusual powers; and Skediceth, a god of white lies who’s bound to Inara."